Sunday, December 31, 2006

'Trading Places' and 'Yes, I'm Asian'

Sonia's piece concerns her transition from medical student to patient and back again when she discovered a malignant melanoma.

Robin's piece examines Asian parental attitudes towards their children's career choice, and the impact on the way those children are later perceived.

Both make for interesting reading and have already received responses through the website's online comment system. Well done!

Thursday, December 28, 2006

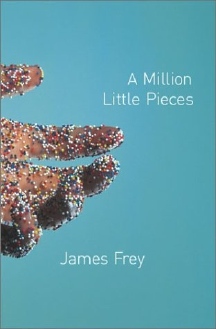

A Million Little Pieces - Review

This dark and honest account of a young man’s attempt to escape the clutches of drug and alcohol addiction is an unforgettable book.

This dark and honest account of a young man’s attempt to escape the clutches of drug and alcohol addiction is an unforgettable book.James Frey is twenty-three, and has been addicted to most substances since the age of eight, with barely a few days of sobriety in fifteen years. Coming-to on a plane with no front teeth, a hole in his cheek and a staggering hangover, James’ long suffering parents check him into a famous rehabilitation centre for what is, to all intents and purposes, his last chance.

The breathless style conveys the sheer mind-boggling emergence through detoxification, with the dream-like hallucinating and internal subconscious priorities manifested. The lack of punctuation, far from making the prose a difficult read, actually gives the idea of a flurry of ideas, the repetitive, consistent desires.

‘A Million Little Pieces’ is no sob story. Frey’s genuine beliefs and initial lack of remorse keep the reader open-minded, and so the pages turn, James becomes an intriguing character that we find ourselves hoping will succeed. His rehabilitation is a rocky road, and the hierarchy within his unit is somewhat similar to a prison.

But James is an unconventional character who maintains his own beliefs, rejecting the conventional Alcoholics Anonymous and the Twelve Steps. Despite the pessimism of the staff, James’ own way ultimately proves the right path for him – his philosophy is simply to decide to stop, not replace one addiction with another (meaning religion) – which brings up an interesting theological debate as well as a discussion on the notion of addiction as a disease.

This book examines interesting issues surrounding drug and alcohol addiction, including psychiatric aspects and multi-factorial risk factors for potential addiction.

This is one of the most powerful and compelling books I’ve ever read; the very fact it is a memoir makes it unbelievably astonishing.

Bodies - Review

Bodies is a visceral, gripping book. It is written in a vein similar to Bedside Stories, but without the humour and return to reality between each instalment – we chart the journey of a Houseman from his first day on the ward, and through his junior years.

Ultimately, this book is the tale of the dark side of doctoring: the cock-ups, covers ups, guilt and strain. It is virtually an anonymous account – we never learn the central character’s name, and mostly the other doctors are anonymised; patients are nicknamed. This does give a disturbing edge of reality – how much of it is, or was, real?

Bodies deals with conscience, the hidden curriculum and red tape, and the insider concept of whistle-blowing – exposing another as negligent, and exposing yourself in so doing.

Mercurio writes extremely well – the book is compelling – and despite its gritty negativity, the tangible sensations described mean this book stands alone from its TV serialisation counterpart.

One wonders, having read the book, about Mercurio’s audience – my medical background meant I didn’t have such a need the glossary (that I discovered upon turning the last page), but even this doesn’t fill the void. I came away from Bodies feeling strongly that Mercurio has a message, a clear and pointed message, targeted at those to whom he can make a difference.

‘Bodies’ refers not only to corpses and death, but also human bodies, alive, anatomical beings. It is almost as if one makes the transition from human body to corpse if one were a Houseman in the book – and the the bodily fluids, secretions and disturbances are encountered along the way.

The catalogue of errors that make up the book serve as a warning and a red flag to future medics; they also go some way to provide an explanation to why things do go wrong, and what results if these errors go unheeded.

We achieve resolution in the book, but not necessarily in the way anticipated or desired. Flashes of humanity come and go in the characters, but as readers we maintain our own throughout.

The Time Traveler's Wife - Review

Audrey Niffenegger's book is a tale spanning a few decades, ultimately concerning the love between Henry and Clare, but also examining Henry’s ability to leave one time in his life and appear in another.

Audrey Niffenegger's book is a tale spanning a few decades, ultimately concerning the love between Henry and Clare, but also examining Henry’s ability to leave one time in his life and appear in another.Despite lacking plausibility, and owing some plot aspects to convenience, this makes for a good book. The author uses the sense of impending doom or imminent danger to create tension and to keep one turning pages.

The style is detailed, with at times over thorough portrayals of methodology in art for example, which clashes with the sketchy medical explanation for Henry’s ability to time-travel. It is written from the point of view of both Henry and Clare which serves to give balance, as the character of Clare is somewhat pure compared to Henry’s darker features.

As well as having a medical slant, the book also has political sympathies, bringing in themes of family, music, art and research, which may seem ambitious but give a rich sense and blend.

Henry has been able to time-travel since a young age, usually unexpectedly and associated with unpleasant effects such as nausea and vomiting. He first meets future wife Clare when she is a small girl and he is middle aged, but in reality they are much closer in age. They form a strong bond and we learn not only what it is like to time-travel (with its related inconveniences) but also what it is like to live with, love and deal with a partner who vanishes without warning, for an unknown amount of time, who may be in danger.

The book reached an interesting peak for me when Henry and Clare try to have a child. The author has explored potential health consequences of such an affliction – Clare suffers multiple miscarriages as her foetuses time travel outside her womb and are immunologically rejected as they re-enter.

‘The Time Traveller’s Wife’ has a broad appeal and is written in a neutral manner, making it accessible to readers from all backgrounds. One always has the feeling of what is about to happen but nevertheless one continues to read, seemingly making the conclusion all the more satisfying.

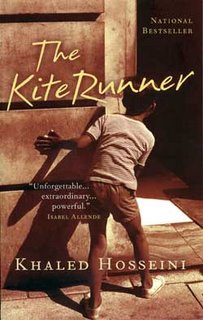

The Kite Runner - Review

Khaled Hosseini's 'The Kite Runner' is a beautiful yet tragic account, which brings together themes of kinship, culture, loss and redemption. Set in

Khaled Hosseini's 'The Kite Runner' is a beautiful yet tragic account, which brings together themes of kinship, culture, loss and redemption. Set in This book chronicles a society in a way crucial to its memory, and its customs, history and characters, and then destructs it through the course of it’s civil war and internal struggles. This has the effect of making those fragments all the more precious, seeing the whole has gone.

'The Kite Runner' is not a happy book, and at times when one feels all is well, heartache is lurking around the corner. Themes of nobility and honour permeate the text giving the book an unpretentious grandness. In a similar vein to the Bookseller of Kabul, the author presents a slice of life in

We follow Amir, the central character, and his relationship with his father, their servants Ali and Hassan, and his father’s friend Rahim Khan throughout his life, and the secret bond that ties them all together.

‘The Kite Runner’ refers to the Afghani tradition of kite fighting and chasing the fallen kites. This serves as a metaphor: running away, coming back victorious; falls from grace; conflict, struggle, glory, but most of all, the play of children, the wounds of glass, the teamwork required.

This is a deeply moving tale, a sad story, but wonderfully written and told.

The Machinist - Review

The opening scene sees Reznik disposing of a corpse and being illuminated in the beam of a flashlight. This sets the scene for Reznik’s odd behaviour during the film and lets us know as the audience that Reznik has or will commit a crime at some stage.

Reznik is thoroughly underweight and his appearance will draw gasps of shock from viewers. He seems to be obsessive – monitoring his falling weight, always going to the airport café late at night, and avoiding sleep.

Essentially he has a psychiatric condition somewhere between paranoid schizophrenia, obsessive compulsive disorder, post traumatic stress disorder and reactive depression, and his journey in discovering for himself what is going on, and the tricks his mind plays on him makes both compelling and fascinating viewing.

Suppressed memories contribute pieces towards scenes played in Reznik’s mind which he experiences as reality, the resulting confusion adding layers and tension to the final ‘reveal’.

The film is an interesting example of the ‘split-personality’ of schizophrenia so beloved by modern film-makers. Despite this being an inaccurate interpretation of the condition, it makes for marvellous screenplay.

The dark and foreboding atmosphere and the paranoid edge are useful to consider the feelings of someone suffering from a psychosis and to provide an explanation for some of their actions and behaviour, although it doesn’t do much for the image of mental health.

Bale is brilliant as the tormented Reznik and his devotion to the role is evident.

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

Seasons Greetings!

Who'd have thought Clooney et al would be involved in a serious study, pitting the attractiveness of surgeons versus their physician counterparts? Read the conclusions of the Barcelona-based study group here.

Ditto the oft-trivialised experiences of doctors as patients. A marriage between medics is one phenomenon seen sporadically at the shrink's, but what about the real psychology doctors experienced when letting someone else take control? The responses to 'Doctors as Patients' are certainly interesting to behold & indeed empathise with, in addition to the thoughts of our Kiwi counterparts on how they think their doctors should dress. There's certainly some food for thought, given the ongoing review in proximal climes.

A Merry Xmas and a Happy New Year to you all - let's take a special minute to raise our glasses in thanks to Giskin for yet another successful year!

Keep Blogging!

Thursday, December 14, 2006

Recollections of child birth

The click of the PCA is comforting in itself,

although my head is thick with morphine and

everything is heavy and confused.

They say I should go and see her

and I suppose I should

but ... I am disconnected.

I drag my body from the bed.

The tubes and wires and monitors come too

and they wheel me down to meet her.

He has to tell me which child is ours -

I don’t know her because I wasn’t there.

She is naked and red, her skin transparent,

covered in down and I still feel disconnected.

She is a stranger and I don’t want to hold her,

but I know it’s expected, so I should.

They hand her to me with her wires and her tubes,

lying in a garish WI crochet shawl,

Someone takes a photo and I try to smile.

Everything feels so far away and I am lost.

This is not how it was in the brochure,

no NG tubes and mainlines there.

My head is spinning and I am screaming inside.

They tell me how well we are both doing.

Can’t they see I am dying inside?

It wasn’t meant to be like this at all.

They put her back in the incubator and

I am wheeled back to the quiet terror of ITU.

I can’t see or hear with any clarity.

The lights are low and soft, perhaps to hide the pain.

Although I repeatedly click the PCA

I am still screaming inside, I wasn’t there,

I wasn’t there and I can’t remember her name.

The whole sordid nightmare loops around and plays again

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

addressing the work, life, bedroom imbalance

Yeah, just like that. Those whose lives are already sold out to children beckon you to join the fold: well, are you going to go on and have another? Are you trying? It never ceases to amaze me how close people can get to asking you about how much sex you are having and thinking about the details of it when they hardly know your name. Something about kids allows an incursion into what was your private life – from the hand on your bump of a stranger on the tube (I’ve had to restrain myself from thumping a few. Restrain, as it wouldn’t look right, from a heavily pregnant woman. Thumping because your instincts are to thwack anyone who so blatantly invades your personal space and is over, say 5 years old) to the sweet ladies in the street who stop you on the pretext of cooing over your baby in order to lecture you on what you should be feeding them and what to dress them in. It is the men who suffer the worst from this. A friend in Boston was accosted by a lady who stopped her car in a blizzard to shout at him for having his baby out (warmly strapped to his front and under his coat) in this weather. Note, she didn’t offer him a lift...

I’m not sure I can blame society and other parents for having three kids in a two bed flat. However problematic this may be, I am seriously starting to worry about going back to working three days a week. It still sounds pretty part time, but there is a huge difference between a sessional job with no responsibility beyond, and being a surgical registrar with responsibility for the firm: on-call patients, the post-op patients, the list, the important ones from clinic, learning and teaching. I know myself now, and I do not have a part-time mentality. Ironic that, when so many full-timers do. I find it impossible to clock off, in fact some of the satisfaction of the job is going home knowing everyone is sorted. And there is the concern about having not operated for what will be three years. The surgical profession rarely has someone back from a maternity leave that has gone on so long, unlike GP or other specialties with women predominating who are having to accomodate real flexible working; however, people do often take out three years to do a PhD/MD (this will soon cease so we are led to believe). Although it is not essential and not monitored, it is assumed that most trainees will have kept their hand in by doing locums during these three years. And then they re-start in the job bang and the system has to cope. My late boss, who’d had some maternity leave herself used to say that the operating comes back easily, like riding a bike. She warned me that it was the judgement that fell behind. At least doing a PhD, you’d come back an expert in a small section of some esoteric bit of molecular stuff that you’d have been to a few conferences to talk about. Your confidence would be high at least on an aspect of the academic side. All I’ll be qualified to talk about is multi-tasking the toddling baby, the new schoolboy’s homework and the older schoolboys nightmares.

At least it is yet a long way off.

I’ll keep the blog posted as the big days near – though even less frequently on the current showing. It’s my last chance to complete my training. I just wonder if I want it any more...

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

The Brain Hospital

Tomorrow evening (Wednesday) sees the second in the BBC1 documentary series The Brain Hospital , set in The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery. The hospital, as you probably know, is a world leader in the research and treatment of brain disorders. So, it's particularly sad that they have to raise money via a charitable foundation to maintain their level of expertise. The program (a series of three) follows some remarkable cases. Last weeks episode was emotional to say the least, but then I'm like that which is why I don't normally watch these sorts of programs! That said, I will be watching again tomorrow at 9pm on BBC1.

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Medical Humanities

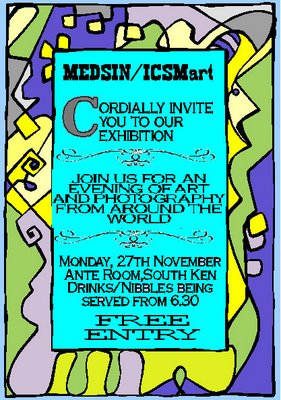

....IC Medsin Society presents....

Positively Red!

AIDS awareness week

This year the week's theme is focusing on stigma and charities we will be supporting are: - Kidzpositive family fund https://icex.imperial.ac.uk/exchweb/bin/redir.asp?URL=http://www.kidzpositive.org - FoTAC (Friends of the treatment action campaign) https://icex.imperial.ac.uk/exchweb/bin/redir.asp?URL=http://www.fotac.org.uk - Children with AIDS charity https://icex.imperial.ac.uk/exchweb/bin/redir.asp?URL=http://www.cwac.org/

We have a whole week of great events lined up starting from Mon 27th November!!

Stalls everyday in SAF and the JCR selling fantastic hand made bead work and ribbons

Art exhibition: 'Around the World'

6.30pm Monday 27th November: Ante Room: Free drinks and nibbles

Debate:"This house believes that HIV status should be public knowledge"

6pm Wednesday 29th November: Lecture theatre B, SAF building

Drinks and nibbles included!

And finally....

A fundraising party at the union on Friday 1st December which is

WORLD AIDS DAY!!!

There will be fabulous music and entertainment including fire jugglers, free condoms and lollies, helium balloons and lots lots more!!!!

The Positively Red Party!!

Fri 1st Dec, 9pm till late

Union, South Ken

Tickets £3

In association with SUB - RED drum & bass

in Dbs/ drink promos all night/ get behind

this great cause on World AIDS day & party!

Raffle prizes/

Free condoms and lollies/

Fire Juggling/

RED helium balloons!

Vodka and draft mixer: £1.25

(£1 from every ticket sold goes to AIDS Week charities)

Friday, November 24, 2006

Art Exhibition

Friday, November 17, 2006

Allopath

Check out this hilarious satirical video by Mercola promoting prevention of environmentally-caused diseases. It's 7 minutes long. I spotted it on the Environmental Illness Resource website, a curious mix of sound politico-medical activism and scaremongering anti-corporate hyperbole. Anyway, the video is well worth watching.

Monday, November 13, 2006

Halloween poet

Literary Doctors' Wives

The doctor was a popular figure in Victorian literature, but served as something of an anti-hero. Literary doctors either lacked ambition (e.g. Charles Bovary in Flaubert's Madam Bovary, George Gilbert in Braddon's The Doctor's Wife) or were thwarted by ambition (e.g. Lydgate in Eliot's Middlemarch). They tended to die young. They were usually reasonably good doctors, but poor judges of character. And, above all, they tend to choose the wrong sort of woman to marry.

The doctor was a popular figure in Victorian literature, but served as something of an anti-hero. Literary doctors either lacked ambition (e.g. Charles Bovary in Flaubert's Madam Bovary, George Gilbert in Braddon's The Doctor's Wife) or were thwarted by ambition (e.g. Lydgate in Eliot's Middlemarch). They tended to die young. They were usually reasonably good doctors, but poor judges of character. And, above all, they tend to choose the wrong sort of woman to marry.The most notorious doctor's wife is undoubtedly Emma Bovary. Her romantic appetite is fed by reading novels (delicious ironic touch by Flaubert), but when married life fails to live up to the 'felicity, passion, rapture, that had seemed to her so beautiful in books,' Emma becomes bored and resentful. She embarks on two affairs, to which her husband remains blind. Eventually, having bankrupted the family, she poisons herself. Her husband, who adores her to the last, cannot save her.

Mary Braddon's plot in The Doctor's Wife, 'borrows' heavily from Madame Bovary. Isabel also finds life as a country doctor's wife exceptionally tedious. She cannot give up her romantic notions, inspired by rather superficial readings of a great many novels. When she meets handsome, gentrified Roland Landsell whose insipid poetry she holds in high esteem, she is enraptured by him (or 'him' for she always thinks of him in italics!). After judging her rather silly and vacuous at first, Landsell becomes besotted with the black-eyed, blushing doctor's wife. Here the plot departs from Madame Bovary in that Isabel does not embark on a full-fledged affair. She is shocked when Landsell suggests they run away together: suicide would have been a suggestion more

worthy of contemplation. This exposes Isabel and Landsell's completely different views on what it means to be 'in love'. Braddon's novel is an indictment of idleness: neither Isabel nor Landsell have enough to do and consequently they fall prey to the excesses of imagination. It ends unhappily for Dr Gilbert and Landsell, and Isabel only finds contentment when she uses her legacy to do good works in the community.

worthy of contemplation. This exposes Isabel and Landsell's completely different views on what it means to be 'in love'. Braddon's novel is an indictment of idleness: neither Isabel nor Landsell have enough to do and consequently they fall prey to the excesses of imagination. It ends unhappily for Dr Gilbert and Landsell, and Isabel only finds contentment when she uses her legacy to do good works in the community. George Gilbert, Isabel's unambitious husband, is similar to Charles Bovary in that both are popular amongst their peasant patients for their lack of pretensions, but neither manages to accurately diagnose or treat their wives -- both of whom demonstrate a range of physical symptoms in response to their unfulfilled romantic yearnings. In common with Lydgate in Middlemarch, who marries the flightly and pretentious Rosamund against his better judgement, these doctors choose women they found fascinating, in rare moments of allowing their hearts to rule their heads. In all three cases, it was almost as if they could not help themselves, although the warning signs of potential disaster are flagged up all to readily. Certainly the reader is acutely aware that the matches are ill advised.

The Victorian literary doctor's wife can be seen as the embodiment of the aspirations of the newly emerging medical profession. Bovary, Gilbert and Lydgate all choose educated but sentimental women who aspire to wealth and position, but find that a country doctor's practice does not afford the means or the opportunity to indulge these fantasies. Moreover, these 'men of science' are rather too practical and inperceptive to cater for their wives' complex emotional needs.

In contrast, I want to briefly discuss a novel also entitled The Doctor's Wife, by Sawako Arioyoshi. Written in 1967 although set in 18th century Japan, the book is loosely based on the life of Seishu, the first doctor in the world to operate on breat cancer under general anaesthetic. Here, the marriage between Kae and Seishu is arranged by Seishu's beautiful mother Otsugi. Kae doesn't meet her husband until a considera

ble time after they have been married (his place in the wedding ceremony is taken by a manuscript of herbal remedies). The instant he returns from his studies an intense rivalry begins between Kae and her hitherto friendly mother-in-law. They both volunteer to for the old fashioned equivalent of a drug trial, offering to imbibe the poisonous mandarage which has anaesthetic qualities.

ble time after they have been married (his place in the wedding ceremony is taken by a manuscript of herbal remedies). The instant he returns from his studies an intense rivalry begins between Kae and her hitherto friendly mother-in-law. They both volunteer to for the old fashioned equivalent of a drug trial, offering to imbibe the poisonous mandarage which has anaesthetic qualities.Although a more successful doctor than Bovary or Gilbert, or even Lydgate, Seishu also is inperceptive in matters of the heart. The rivalry between Otsugi and Kae is never acknowledged, and he also fails to save either of his sisters from dying of cancers. In contrast to Victorian novels, idleness of the part of the doctor's wife is not an option here. The entire family work like slaves to pay for Seishu's education and to support his experiments and philanthropic doctoring in times of famine. Kae is a flawed heroine. Although she ends up sacrificing her eyesight to help her husband's career, she must confront the realisation that it was an act of triumphalism over her mother-in-law rather than a truly noble sacrific for her husband. A minor criticism is that the book suffers from overly blatent hindsight. Seishu articulates the uses of anaesthesia far too neatly in advance of his experiments. Nevertheless, the descriptions of Japanese values and the honour system, and how medicine and human foibles interact with this sytem, make this novel a fascinating and compelling read.

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Long Life and Happiness?

Catch this series of events run by The Wellcome Trust over the coming weeks. Wellbeing in the 21st Century Winter discusses issues such as :-

What is happiness and why is everybody taking about it? (28th Nov)

Can medicine deliver what you want for future health and happiness? (5th Dec)

What happens when music meets the mind? (11th Dec)

Tickets are free but must be booked by calling 020 7611 8442 or email events@wellcome.ac.uk

Sunday, October 29, 2006

DOCTORS MAKE DRAMA

Friday, October 27, 2006

Nick Silver Can't Sleep

Although not without interest, I found this Radio 3 play on insomnia oddly soporific! Janice Kerbel's Nick Silver Can't Sleep is part of Artangel's Nights of London series of artist-led projects exploring the city with people who wake, work or watch over it. Kerbel developed her project in conversation with insomniacs, sleep scientists and botanists. Listen again here after 4th November.

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Metamorphosis

Franz Kafka's modern classic Metamorphosis is showing at the Lyric theatre in Hammersmith until Sat 28th October.

The bizarre tale of a man who wakes up to find himself turned into a giant spider and his family's response to this comes alive beautifully on stage. Set to an original, haunting soundtrack, the 2 storey stage allows the audience to simultaneously experience the changing reactions of the family from fear and disbelief to transient kindness followed by negligence and downright ruthlessness , alongside the increasing isolation and suffering of the transformed man.

I was struck by the parallel situation of various people with chronic diseases such as cancers but also mental illness, which is heavily stigmatised because it is so poorly understood from both the clinical and public perspectives. I found the sense of betrayal by the sister was particularly poignant, in contrast to the denial and indifference exhibited by his parents.

With the exception of a few humourous interludes (I think designed to take the edge off the raw emotions felt by the audience), the play stays faithful to the story. Incredibly powerful - well worth seeing.

Friday, October 20, 2006

Review: 'The Blackwater Lightship' by Colm Toibin

It’s the early 1990s in Ireland and a young man, Declan, is in the final stages of AIDS. He has hidden his homosexuality and his illness from his family until now. His sister Helen, through whose eyes the story is told, his hard-bitten mother and his proud and obstinate grandmother will all react in different ways. Helen has never forgiven her mother for her utterly inept handling of their father’s death from cancer twenty years before, which left her feeling unloved and emotionally isolated. Now Declan wants to spend a few days in his grandmother’s house on a crumbling cliff in Cush and the family is reluctantly forced together to support him. His friends Paul and Larry are mercifully competent at dealing with the physical exigencies of illness and prepared to put up with the family’s hostility.

It’s the early 1990s in Ireland and a young man, Declan, is in the final stages of AIDS. He has hidden his homosexuality and his illness from his family until now. His sister Helen, through whose eyes the story is told, his hard-bitten mother and his proud and obstinate grandmother will all react in different ways. Helen has never forgiven her mother for her utterly inept handling of their father’s death from cancer twenty years before, which left her feeling unloved and emotionally isolated. Now Declan wants to spend a few days in his grandmother’s house on a crumbling cliff in Cush and the family is reluctantly forced together to support him. His friends Paul and Larry are mercifully competent at dealing with the physical exigencies of illness and prepared to put up with the family’s hostility.Colm Toibin’s writing style is deft and engaging. One cannot help but hear the Irish accent in his dialogue. ‘Oh look who it is now, look at her, look at her hair!’ shouts Granny at a panelist on the The Late Late Show. There are plenty of humorous interludes to lighten what would otherwise be a rather solemn narrative.

The decommissioned Blackwater Lightship of the title is a metaphor for the unfathomable loss of something expected to be consistently dependable – like the love of a mother or daughter.

The doctor, although she doesn't feature prominently in the story, comes off refreshingly well in this account. She is a consultant known to her patients as ‘Louise’. She’s given out her home number and is caring, worried and engaged in spite of the inevitability of Declan’s condition. Declan's friend Paul was medically literate in a way that seemed a credible and respectful reflection of the knowledge carers acquire through proximity and experience with chronic illness.

I didn’t know that this novel included an illness narrative when I plucked it off the shelf. I can recommend it as a lyrical account of family relationships in times of crisis.

Friday, October 13, 2006

'A Pervert's Guide to Cinema'

Behind the rather ambiguous title, A Pervert's Guide to Cinema is a brilliant documentary film about cinema and the psyche. The endearing and engaging Slavoj Zizek, Slovenian psychoanalyst and philosopher, takes us on a magical demystifying tour of how films play on notions of fantasy and reality. Zizek uses psychoanalytic concepts, but explains so clearly with apt clips from a range of films, that no one should be deterred by the theory.

Behind the rather ambiguous title, A Pervert's Guide to Cinema is a brilliant documentary film about cinema and the psyche. The endearing and engaging Slavoj Zizek, Slovenian psychoanalyst and philosopher, takes us on a magical demystifying tour of how films play on notions of fantasy and reality. Zizek uses psychoanalytic concepts, but explains so clearly with apt clips from a range of films, that no one should be deterred by the theory.The film, which I should warn you is long, is divided into three parts. Part 1 deals with the workings of the unconscious in movies. It maps the way film uses Freudian concepts to confront anxiety, and of this Hitchcock is exemplary. Part 2 looks at desire: this part is particularly persuasive about how fantasy is used to escape reality but when fantasies become real they are even more nightmarish than reality. He draws on Solaris, The Piano Teacher and David Lynch's movies to demonstrate. Part 3 is about illusion. We know film is an illusion but why do we still find it so convincing? Zizek shows how even when we know what will happen, we still are drawn in by the subjective experience of spectatorship.

What makes this film so much more than a lecture, is that Zizek travels to locations and interperlates himself into the sets of the movies he discusses. Zizek's style is witty and frank, and his emotional intesity on screen makes him as good a performer as any RADA-schooled actor. Probably predictably, he draws mainly from the horror genre which lend themselves most readily to Freudian/Lacanian concepts of subjecthood, but the array of films referred to is wide: The Matrix, Eyes Wide Shut, Blue Velvet, The Tramp, to name but a few

Fascinating, enlightening and enjoyable -- everyone interested in film and representation should see this movie. I recommend seeing it in the cinema as the clips have much more presence than on TV. But if you can't make it to the ICA before 2 November and you're interested in the ideas, an edited transcription is here.

Thursday, October 12, 2006

StudentBMJ is well worth a look

In the same issue is an article by James Thomas from Leeds on the value of creative writing and poetry to medical education. Hear, hear!

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

Test Site 2006

Not so much a coathanger round an old sock as a rat down a drainpipe! Sorry, I know it's not exactly relevant to medical humanities but Tz's last post and The Guardian's piece on this new work in the Tate Modern's Turbine Hall just seemed to coincide - serendipity or what? It's Test Site, Carsten Holler's latest at Tate Modern. Apparently you reach speeds of 30mph as you descend. God only knows what that does to you. I feel a PCC outing coming on!

A coat-hanger round an old sock

I am inspired to write because for the last two hours in between breastfeeding my teething baby back to sleep, I’ve been filling in the details of my colonoscopies of the last few months on an Excel spreadsheet. Mind-numbing, hence the break. However, it has set me thinking. I had a break from even this for a year to have my baby. At present I am entering the data from before I left to have her. My success rate is quantifiable - and I have just, after 3 months, made it back to pre-baby levels.

The colon is a long loopy thing. Passing this bendy tube round it is just difficult enough to be a challenge (luckily for the patient, or not, depending on your view). It is akin to trying to pass a coat hanger through a very long sock with your eyes shut. And, like surgery, you don’t mind doing the same thing again and again if it is complex enough, as there is a satisfaction to doing this well, and a motivation to keep improving and making it more efficient, or more elegant. I remember timing my appendectomies until I had done one in 25 minutes from first incision to finishing sewing up. After that, I felt cutting the time down further would be a triumph of bravado over safety so I stopped timing. The next challenge came with perfecting the size of the incision, and then with training others. I have spoken to some old greybeards who say that it all palls in the end. And all you are left with is the money. But that would be cynical.

The process of learning is predictable. There are known, anatomical bends in this thing and they are like markers of your learning curve. First, get out of the rectum my dear. This is particularly hard in women who’ve had a hysterectomy (so they say... this may just be the kind of surgical folklore which is brought in to buttress up one’s ego after failing at something). Indeed, one of my first bosses used to give me 3 minutes (the time he could, bravado all the way, make it all the way round in) at the beginning of each colon. I spent 3 months up the recta of half the population of that small seaside town before I ever made it out of a rectum... And so it goes on. Splenic flexure, hepatic, and that final hurdle, the ileocaecal valve. Despite being at separate ends of the scope, with very different opinions as to whether it should be advancing or withdrawing, you and the patient jointly cheer when it gets to the end – the delightful sight of the only recognizable bit of bowel drawing into view like a long-awaited harbour: the caecum. I even don’t mind a bit of the brown stuff here (very un poo-like and liquid. The scope ensures there is very little smell, and when you turn the hepatic corner into the last lap, often with difficulty and a sense of triumph, the poo has also, you note, been struggling to make it round the corner. Its lakes are a welcome sight of homecoming.)

Perhaps I haven’t mentioned colonoscopy because its outer reaches (inner reaches) are not for the faint-hearted. Indeed, they might make you think I was weird.. Well, I am glad to say that for once I was joined the whole trip round by a patient who was just as weird the other day. He’d had some of the usual jollop which I often suspect is over-dosed in order to render the patient a proper, asleep well-behaved patient who doesn't interrupt. Only, occasionally it has the paradoxical effect of inducing intense garrulousness. One of the recognised jobs of the endoscopy nurse is to take over talking to the talkative patient so that you can get on with the test. Serious. This patient, however was different. He was interesting. At least, many may be interesting only one doesn’t have time for small talk when one is wrestling with the splenic flexure. But he was interested in what he was seeing. So are many patients of the well-informed, not hung-up variety. But this bloke was just free-forming. Never has the inner landscape been so variously described and discussed. It was an alien territory. It was – as I explained, commonly referred to by us as looking like a Toblerone – the transverse colon. He was ecstatic over that idea and all forms of chocolate were dredged up and became parts of the colon: the Roses green triangle, Curly-Wurly, the inside of an easter egg... We passed the liver - give us a wave! And detected all his recent abuses of that organ. We were underwater, pot-holing, finding caves over little pink crests of bowel. Like the inside of an accordian. We were – somewhat like the part of the Tracey Emin film “Top Spot” where a girl is lost in endless tunnels with a carnivorous predator spotted padding forward – we were in tunnels. Trains, buses (the bendy buses of course). He wanted to know what everything was, every little ridge and vessel and streak of tomato. I’d found a fellow enthusiast. We could have been a team. Only his colonoscopy – thankfully one twinge only at the splenic – was normal. He had no indication for one again in the forseeable future. Sigh. A perfect partnership briefly twinkled, and was gone.

Monday, October 09, 2006

Inside Mental Health

This week sees an Inside Out London special to commemorate Mental Health Week. It promises to explore the lives of the mentally ill and investigate cutbacks in the mental health system. Sarah Tonin (pictured above), is just one of the cases examined. Sarah courageously admits that "the world has always been a scary place". She has been battling with mental illness for 38 years experiencing a range of different psychosis from agoraphobia to hallucinations. You can read more about Sarah and others here. The half-hour program will screened on BBC1 this evening at 7:30pm.

This week sees an Inside Out London special to commemorate Mental Health Week. It promises to explore the lives of the mentally ill and investigate cutbacks in the mental health system. Sarah Tonin (pictured above), is just one of the cases examined. Sarah courageously admits that "the world has always been a scary place". She has been battling with mental illness for 38 years experiencing a range of different psychosis from agoraphobia to hallucinations. You can read more about Sarah and others here. The half-hour program will screened on BBC1 this evening at 7:30pm.

Friday, October 06, 2006

Tracey Emin subjected to our gaze

such as smell, taste and touch. The picture can be viewed in a double frame of reference, as a vulnerable girl who has been the victim of abuse, but also with the connotations of Tracey Emin, the provocative artist, whose work seems somehow 'stuck' in her adolescent experiences. Using very traditional iconography in a self-reflexive fashion, Emin denies any voyeuristic look by invoking the other senses. The vulnerable child, for example, returns the smell of fear, and denies any caress however tender. The articulate artist, however, screams out loud and the sweet smell of freedom to voice her position fills the air.

such as smell, taste and touch. The picture can be viewed in a double frame of reference, as a vulnerable girl who has been the victim of abuse, but also with the connotations of Tracey Emin, the provocative artist, whose work seems somehow 'stuck' in her adolescent experiences. Using very traditional iconography in a self-reflexive fashion, Emin denies any voyeuristic look by invoking the other senses. The vulnerable child, for example, returns the smell of fear, and denies any caress however tender. The articulate artist, however, screams out loud and the sweet smell of freedom to voice her position fills the air.We watched Emin's film, 'Top Spot'. It is an intriguing work which combines a variety of representational approaches. It features a group schoolgirls, first shown being interrogated (by Emin, off-camera) about sexual experiences. Although the girls look 'innocent', many have traumatic or shocking stories to tell. There are no male characters -- these are alluded to rather than realised -- although phallic symbolism abounds. Bleak scenes of the Margate beachfront are interpolated with scenes of Egypt where one of the girls apparently goes to try and track down her lover (although it is never clear whether this is a fantasy or not). The film has an unsettling climax which, like some of the preceding scenes, is shrouded in ambiguity.

The discussion after the film involved a lively discussion on role of autobiography in art, and what came across as convincing or contrived in the narrative. The sexualisation of the girls, portrayed as normative, was perhaps the most striking theme. Although the film was undoubtedly shocking, there was a sense of detachment because the viewer is never really drawn in sufficiently to identify with any of the characters. The camera technique never adopts any of the girls' point of view so the viewer is permanently in the uncomfortable role of voyeur.

Views on Emin's work in general were divided: some expressed grudging admiration for her ability to be so successful in spite of what might be perceived as a dearth of conventional artistic talent, others were infuriated by her inability to 'move on' from evoking her teenage experiences in her art. Is she brave to expose her life to public gaze -- the details of which many people find distasteful?

Emin's work does offer an insight into a particular slice of British life that is depressingly accepting of exploitation as unexceptional. The medical system doesn't even begin to engage with teenagers who seem to consider it unthinkable to submit to any kind of supervision. As Anna pointed out, the film and the issues it raises could help doctors not be complacent about the backgrounds of some adolescents. Ellen highlighted the awkward position of the teenager in the medical system: suitable neither for the adult ward nor the paediatric setting.

Thanks very much to Beth for giving us a theoretical framework with which to think about the positioning of the gaze in art in general and Emin's work in particular.

Sunday, October 01, 2006

Manic Depression

As someone with a close relative who suffers from the condition, I was interested to hear Radio 4's Case Notes present a program on manic depression recently. The program gave some insight into treatment regimes, lifestyles and therapies which might help in managing the highs and the lows. I began to appreciate how the cocktail of mood-stabilizers, anti-depressants, sleeping tablets and anti-psychotics might help, if the sufferer remembers, or chooses, to take them as prescribed. Sufferers shared their experiences and talked candidly of what the episodes of mania and depression felt like for them. Mood stabilizers do what they say, that is smooth out the highs and lows. A sufferer I know personally told me once that the medication just makes her more acceptable to society at large. It numbs her and life is difficult - she misses the manic episodes when she felt on top of the world. You can listen to the Radio 4 take on things again here.

Exciting new blog on the scene

Top Spot

At the next meeting of the Purple Coat Club I will have the pleasure of introducing the work of Tracey Emin. Emin isn't part of my research but just one of those artists whose work never fails to engage my interest. Emin came up recently on this blog in a discussion around abortion. It struck me then that while her work does not portray medicine as such, it certainly engages with some themes and issues of interest. Abortion, rape, abuse, to name but an unpleasant few. Many have accused Emin of a kind of narcissistic self-interest in her work which goes no further than that. I've never taken that view myself for I believe she has much more to say. Anyway, on Thursday 5th October I will briefly introduce her work then show her film Top Spot which recently came out on DVD. Love her or hate her, everyone has a view on Emin, so I am looking forward to a live discussion after the viewing. See you there.

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

The Place Prize for contempary dance 2006

Jonathan Lunn:

‘Self Assembly’

Lucy Suggate:

‘Post Card’

Federick Opoku Addaie:

‘Silence Speaks Volumes’

Luca Silvestrini:

‘B for Body’

Of the four Lucy Suggate’s ‘Post Card’ was the highlight for me. This challenging, emotionally charged dance revolved around an intimate dance trio. James O’Shea’s performance with use of only his upper body, in a wheelchair since losing his legs in 1998, was particularly impressive. In an age where many don’t know quite how to react to disability, dance can be an important and novel medium for communicating the strength, normality and sexuality of the body despite its lack of two limbs. O’Shea was agile and spectacular making full use of the two poignantly empty pink leotard legs as he moved fluidly from sheepskin rugs, to the wheelchair and backs of the other dancers. While still donning their leotards, it was clearly a show of eroticism with a sensuous sinuous dance. It was a daring subject matter for Lucy Suggate to choose. Perhaps it was too challenging for the audience, upon voting it was surpassed by the likes of ‘Self Assembly’ and ‘B for Body’. Was it too risqué? Perhaps. The British sea side theme involving cinema projections upon three background screens further contributed to the hedonism. It was however a little incongruous and if excluded a more interesting, powerful focus on sexuality in the case of disability would have been evident.

Saturday, September 23, 2006

Be a couch potato this week...

On Monday, Channel 4, 9 pm is a Bodyshock episode called 'Kill me to cure me', on the use of hypthermic cardiac standstill to operate on a brain aneurism. One can only assume it was successful, otherwise it wouldn't be on TV. Stay up or record 'Regeneration' at 11.45 pm on BBC1, the acclaimed movie of Pat Barker's prizewinning trilogy.

Also on a ment

al health theme, don't miss the second part of Stephen Fry's 'The Secret Life of the Manic Depressive'. The first part last week was excellent. Fry, who is undoubtedly a national treasure, speaks movingly and honestly about his bipolar disorder. He interviews his luminary friends plus people unearthed by researchers, all of whom have enlightening stories to tell. Fry is outstanding as a narrator. He maintains a sense of scepticism alongside his wry sense of humour. It's a privilege to have an insight into what is clearly a painful personal journey. It's on BBC2 at 9.00 pm.

al health theme, don't miss the second part of Stephen Fry's 'The Secret Life of the Manic Depressive'. The first part last week was excellent. Fry, who is undoubtedly a national treasure, speaks movingly and honestly about his bipolar disorder. He interviews his luminary friends plus people unearthed by researchers, all of whom have enlightening stories to tell. Fry is outstanding as a narrator. He maintains a sense of scepticism alongside his wry sense of humour. It's a privilege to have an insight into what is clearly a painful personal journey. It's on BBC2 at 9.00 pm.On Thursday at 9.00 pm on C4 is a Dispatches episode on 'that drug trial' that went horribly wrong. This is a fascinating story, not least because the patients themselves couldn't speak for themselves for days after the catastrophe. Reasons of taste prevented pictures of the so-called 'elephant men' being published at the time, it will be interesting to see what is showable and what is sayable after the event.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Layers of Unreality

It reminded me of past moments where layers of unreality had been exposed.

The first time, after 2 years of the medical sciences course I spent a year doing English. A rote-learning sponge waiting to be told what to think next, initially I turned up hopefully to every lecture, all 2 of them every week. Insecure, unjustified in any opinion, I was by turns fascinated by the texts and appalled that I was supposed to construct a 15000 dissertation out of them. Then I arrived at medical school after eventual conversion, a mere year later, into a fully-fledged English student, black polo-neck and all. Immediately I was an undercover agent about to lift the lid on medicine from the inside and report back to the real world. Medical training as they’d never imagined it to be. They, the normal people, the non-medics. Of course, it has been done to death since then. Though less of the waiting around for non-existent registrars in canteens and the jockeying for position, by turns hiding at the back and jostling to the front. More of the dramatic stuff of medical student life – admittedly few and far between – call it televisual artistic licence.

Now I recognise these shifts in perception and can carry on through them with hardly a jolt, even enjoy the moment. I waited outside my house tonight for twenty seconds to do just that, as I’d walked home from work thinking like a doctor, being 90% doctor with the facts of the rest of my life attached, as on a CV. Then outside I had to readjust to being a mother, which is more than 90%, it is total. To your kids, whatever else you do as a parent, it is just a name, something to remember like the fact you support Arsenal. One they might get muddled up. One kid knew at 2 that I was a surgeon. However, at 4, after a term of school, he was convinced mummy was a nurse.

Things have changed, though. When our second patient, an anxious Scots bloke, was shown in he chatted happily to the middle aged Indian guy who’d let him in while I sat at the computer finishing off the endless clicking that one patient entails in various programmes that don’t communicate with each other. Eventually I rose and went to introduce myself and he did a double-take. The nurse was quicker than me: “oh, she is the doctor. I am a nurse”. I hoped for a laugh when I said how we’d all swopped genders these days but you could see his discomfort as he readjusted. Perhaps it will be less easy for 4 year olds in the future . 70% of graduates are women and most are sensible enough to head straight into general practice – most of the doctors the 4 year olds see will be women.

At work there was the Rastafarian, manly as they come, resisting any analgesia for his colonoscopy but then, “get this ting outta my body!” In fact there were a few issues of withdrawn consent – a lady from the ward whose veins had given up and gone home. She yelled and the boss said, oh we are nearly there and, “you don’t want to have to come back do you?” and she yelled some more and we all got uncomfortable. But we were nearly round. She was unsedated, so in the end, her absolute instruction to stop was un-ignorable. I’ve always felt that dilemma with the objecting sedated patient given that they will probably not remember objecting. When do you take a single mumbled, “stop” and when does the protest constitute withdrawn consent? When the list is over-running?

There was a doctor-patient, who had to be jolly as he was one of us, then couldn’t help but show pain. Letting the side down. Of course without question we got the boss to do it. “The least we can do”. The NHS insurance plan, unwritten, that as a doctor (mind, it depends on your grade..) you’ll get business class treatment at least. From the doctors. I suspect that this is reversed for example by midwives – there was a malice in the way a certain midwife treated me in labour that I’m sure was exacerbated by the “Doctor” someone had written without my knowledge on my card. I insisted on having the Registrar for my tear. It may not have been sewn up any neater, but I exerted the right of my profession - to be treated by one who knew at least as much as me.

Of course, there are times when you’d rather have the junior doctor than the boss – for example running your cardiac arrest (the boss is usually out of date unless he’s an ITU specialist). And I tried very hard to avoid doctors altogether for my next labour – but also kept quiet about being medical.

Lawyers are also granted special treatment. Often the boss will take over. Extra careful consenting. Special mention of every complication, with exaggerated risks. Their mental health may suffer, but we can’t be too careful. They may, like their medical fellow patients get over-investigated and medicalised, iatrogenically injured, but we can’t be too careful...

Then there was the young man who was an Orthodox Jew. Unthinking, I went to shake hands. Both with him and then, forgetting, with his father later. He wouldn’t. I didn’t dare ask what they thought about a non-Jewish woman doing an invasive colonic procedure but wish I could know. There wasn't a means to find out. You could argue also that by asking, I’d have changed the question. As discussed at the conference – medicine as experienced by patients, of all cultures, religions and professions has a different history to the received history of medicine. And yet, the process of retrieving that patient-led experience changes it, especially, I fear, if the asking is done by a member of the profession.

We had the experience but missed the meaning. That is what medicine was all about, my undercover report seemed to conclude. And they aren’t worried, the trainers. The ideal is not to think about it too closely. In fact the consultants who trained me would fit better with

had too much experience but deliberately (dis)miss the meaning

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

I knew I should have got his autograph!

Tom Reynolds of Random Acts of Reality has published a bestselling book based on his blog as a paramedic. In an act of sheer altruism, he insisted that it be made available free as an e-book which you can download here. But do buy copies for your friends for Christmas (Amazon's got it at £3.99), because he deserves the royalties! Tom came to Purple Coat Club last year to talk about Safelight by Shannon Burke (with which he was unimpressed). He blogged about the experience here. He's a thoroughly nice guy and I hope his book does well. He was talking about it this morning on Radio 4's Midweek.

Monday, September 18, 2006

Medical Humanities conference

In his talk Wiltshire argued that the 'true' history of medicine has not yet been written: what we have is a history of profession and institutions. History is made up of narratives, but the performative act of medicine robs the patient of the opportunity to shape his/her own story into narrative (for Wiltshire, narratives are primarily written, addressed to a reader and involve an intellectual presence that mere story does not). The 'true history' of medicine is the formal patient narrative which also serves as a valuable critique of medicine, for example Fanny Burney's description of her mastectomy. In the interesting discussion that followed, Gilman said narratives don't necessarily reflect patient reality, they are are patients' encounters with 'the system' and are no more 'true' than other types of narrative. Patrica Law weighed in with the observation that there is a wealth of patient narrative available on the internet (notably DIPEx) which suggests that the patient's unmediated 'voice' is more readily accessible.

The following morning it was Sander Gilman's turn to deliver his address, entitled: 'What is the colour of the gonnorrhea ribbon? Stigma, sexual diseases and popular culture in George Bush's world.' Gilman made a fairly complex argument about shame and political activism. He used as his text a novel aimed at young adults called 'The Rainbow Party' which met with a barrage of criticism because it dealt with oral sex (read the conflicting reviews on Amazon.com to get a flavour of the controversy) in the context of a politically charged debate about what exactly constitutes 'sexual relations' and the abstinence culture. Gilman linked the success of AIDS and cancer ribbons with the successful dissociation of the infected with the means of infection (so one identifies with the sufferer rather than the manner in which the patient became ill). Gilman showed how surveys of sexual activity share with novels the ability to offer an insight into attitudes and fantasies. He argued that STDs would never have a 'ribbon' because of the shame culture. This time John Wiltshire weighed in with a comment about the dubiousness of using 'trashy' novels to talk about social trends, whereas surely proper literature was what could and would effect change (I paraphrase). This caused both tutting and nodding in the auditorium.

At the root of the disagreement between these two distinguished authors, I think, is the notion that for Wiltshire, it is important to give certain narratives priority over others. For Gilman, this ranking of narrative is untenable. Personally, I'm in favour of all narratives contributing to an understanding of attitudes. I don't think 'proper literature' should claim priority in critical analysis, although I accept that in practice it probably does.

There were a lot of thought-provoking sessions at the conference. The full programme can be downloaded here. Borneo Breezes asked how AJ and my session on medical blogging went. We had a lot of interest in our talk, although I hope we didn't put people off by cataloguing the ethical pitfalls in blogging medicine. We couldn't cover much in the 14 minutes allowed but hopefully we gave people a taste for all the good stuff out there.

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Events at the Dana Centre

Coming up in the next few weeks:

Lifting the Lid on Radiation Risks, 19 September, 19.00 to 20.30

Art of the Brain, 21 September, 18.30 to 21.30

Criminal Minds?, 27 September, 19.00 to 20.30

Senster, 28 September, 19.00 to 20.30 (billed as 'a spine-tingling perfomance that mingles music, art and artificial life')

'You know it makes sense!', 4 October, 19.00 to 21.00 (Red Rinding Hood is put on the psychiatrist's couch)

Personal Identity, 16 November, 19.00 to 20.30 (Baronness Greenfield explains what's human about identity)

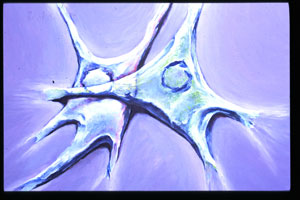

I attended last year's 'Art of the Brain' workshop and can really recommend it. It brought together a biochemist-turned-artist (Lizzie Burns) and various neurologists and brain specialists, including pop-scientist Mark Lythgoe. The audience was eclectic but had in common a sense of apprehensiveness at getting to grips with paintbrush in the services of science. An excellent introductory talk by Lythgoe argued that we must be uninhibited if we are to be creative. He used various examples of how some people had bec

ome very artistic as a result of damage to the fronto-temperal lobe. The disinhibited mind doesn’t screen out so-called irrelevant detail but lets through unfiltered stimuli.

ome very artistic as a result of damage to the fronto-temperal lobe. The disinhibited mind doesn’t screen out so-called irrelevant detail but lets through unfiltered stimuli.So with the message that we had to let our minds be disinhibited (but fortunately without being literally bashed over the head), we were dispatched to various creative workshops. There was a wealth of materials on offer. Downstairs we created neural paintings. Inspired by images of Lizzie’s work (pictured) and colourful micrographs of neurons, we got busy with paints, pastels, crayons and glitter glue to create a picture inspired by the senses. Upstairs, there were workshops which involved articulating ‘hopes and fears’, and making a memory map (drawing a silhouette of your profile and drawing or writing memories in it). There were also drop-in workshops involving palpating gorgeous polymer clay.

Lizzie had never worked with adults before and was somewhat anxious about how the workshop would go, but as far as I could see it was stunningly successful. At the end, Lizzie wanted to know whether we’d learnt something about the brain. I’m not sure whether this should have been the overriding objective. Indeed, some people may have come away with the impression that neurons are found only in the brain – this would have been my impression had I not studied zoology in the dim and distant past. However, I did learn more about myself, and this surely constitutes learning about the brain.

No Obvious Trauma - Review

No Obvious Trauma is a play set in a mental institution in 1933. Two doctors, Dr Weaver and Dr Crawley go about their work, discussing patients and researching papers for their upcoming conference. They are young and optimistic, with hopeful aspirations for their asylum.

One day, a new patient, Ruth, arrives. She flummoxes Dr Crawley with her lack of speech, and he endeavours to investigate her condition.

However, when Dr Weaver sees her for the first time, it sends him on a spiral of memory, missed opportunity and lost love, for she is the very image of Charlotte, with whom he was romantically entangled whilst in Zurich in the past.

The play is a visual delight, combining dance, puppetry and simple sets with tea-dance music and clever use of the sparse stage - drawers become suitcases, wheels of a train, screens are doors, receive projections and provide sillhouettes.

The small cast provides the atmosphere of the echoing-corridor asylum nicely, with strong, slick performances from each actor. Ruth in particular gave a convincing performance of cortorted anguish and rigid fear. Her 'melting' during the course of the play is synonymous with her healing and improvement.

Ruth's condition is based on hysteria and within the play we see the susceptibilities of different personalities to emotional ties and classical themes, such as the over involvement of doctor and patient. I was struck by the dedication of the doctor to his patient, whether alluding to flaws in our modern system or merely praising the old traditional practices.

No Obvious Trauma is an ambiguous tale, with much left open to the imagination. The plot approaches cliche without crossing that line, and in that respect I felt the first act to be more thrilling and satisfying - the manner of explanation in the second act is a difficult plot sequence to convey.

The puppetry reminded me of the 1999 film Being John Malkovich. The use of light and shadow gave the performance a sinister edge, perhaps alluding to the power a doctor wields over his patient, especially given the context of a mental institution. Overall, this was a very enjoyable show, and I would thoroughly recommend it.

Saturday, September 09, 2006

Skypecasts

Skype, a popular service that provides free voice calls over the internet, has been begun offering a new product allowing users all over the world to participate in real-time discussions with others about... well anything! The preview service, still in beta form, allows you to search for and join a conversation with people also interested in that particular topic. You can then voice your views after being handed the "microphone", all from the comfort of your own home.

Skype, a popular service that provides free voice calls over the internet, has been begun offering a new product allowing users all over the world to participate in real-time discussions with others about... well anything! The preview service, still in beta form, allows you to search for and join a conversation with people also interested in that particular topic. You can then voice your views after being handed the "microphone", all from the comfort of your own home.This is a new move for the rapidly growing telephony giant, which is famous for its disruptive technology that brings its users closer together through free Skype-to-Skype voice and video calls, and extremely cheap calls to landlines and mobiles across the planet. The new addition to the Skype phenomenon is called Skypecasts, allowing people who download their free software to broadcast their opinions to listeners, like a radio show where you choose the topic you want to discuss.

Recently a number of Skypecasts about medical literature have been quite popular, including one about Geeta Anand's new novel "The Cure" about "How a Father Raised $100 Million--And Bucked the Medical Establishment--In a Quest to Save His Children". This was a popular Skypecast with listeners and contributors from the USA, India and other corners of the globe.

This new form of conversing with others has taken off: authors such as Anand using it to raise publicity for their work, and bloggers have started using it as a more direct form of expression and contact with their readers. Others have used Skypecasts to share their views about access to health care.

Perhaps this is a tool that could be used in the future by support groups, medical associations and even conference organisers. After all, it's free!

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

Travelling Apothecary

As part of the London Design festival, the Wellcome Trust has commissioned a one-day event - Travelling Apothecary - to be held in the Piazza of the British Library between 1000 and 1800 on Saturday 16th September. Stalls at this free event will offer cures for everything from 'network addiction' and 'litter guilt', to 'fantasy flings' and 'home makeovers'. You can find out more here.

Personally I'm quite drawn to Dr Bettler's Network Addiction Herbal Drink, sure to cure all blogging ills! Apparently Dr Bettler (aka graphic designer Alexandre Bettler) is currently working on a project about bread as a means of communication.

Monday, September 04, 2006

Ways of Dying

This is Marc Quinn's work Template For My Future Plastic Surgery (1992). It is used by the Tate to represent a half-day symposium, Ways of Dying, which will be held at Tate Modern on Saturday 14th October from 1400-1930. It will explore the relationship between life and death in contemporary cultures, drawing on the fields of art, philosophy, law, medicine, political theory, gender and cultural studies, biotechnology and environmental sciences. The program shows a top class field of speakers and papers. Oh, and there are drinks and music afterwards. You can find out more and book tickets here.

This is Marc Quinn's work Template For My Future Plastic Surgery (1992). It is used by the Tate to represent a half-day symposium, Ways of Dying, which will be held at Tate Modern on Saturday 14th October from 1400-1930. It will explore the relationship between life and death in contemporary cultures, drawing on the fields of art, philosophy, law, medicine, political theory, gender and cultural studies, biotechnology and environmental sciences. The program shows a top class field of speakers and papers. Oh, and there are drinks and music afterwards. You can find out more and book tickets here.

Sunday, September 03, 2006

Baghdad ER

Showing on More4 on Wednesday night is Baghdad ER, an Emmy-winning documentary about the 86th Combat Support Hospital, a US army facility in Iraq. The 60-minute film is controversial. US army representatives refused to attend a screening because they thought it would engender negative feelings about the war. (As if any coverage of Iraq might engender a positive attitude.) The Army Surgeon General also issued a warning that if ex-combatants watched the film, they could suffer from post-traumatic stress. I have a feeling that watching this documentary might make all the 'gritty' medical and/or war dramas seem a pale shadow of reality.

Showing on More4 on Wednesday night is Baghdad ER, an Emmy-winning documentary about the 86th Combat Support Hospital, a US army facility in Iraq. The 60-minute film is controversial. US army representatives refused to attend a screening because they thought it would engender negative feelings about the war. (As if any coverage of Iraq might engender a positive attitude.) The Army Surgeon General also issued a warning that if ex-combatants watched the film, they could suffer from post-traumatic stress. I have a feeling that watching this documentary might make all the 'gritty' medical and/or war dramas seem a pale shadow of reality.I am in two-thirds through reading the Regeneration trilogy by Pat Barker. It is a tightly written and well-researched series of novels that focuses on the psychological treatment of soldiers in World War I. Barker uses the lives of the famous war poets, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, and their relationship with psychiatrist William Rivers as the basis for her books. She brilliantly merges biography and imaginative writing to explore issues of conscience and psychosis. I particularly like the snatches of poetry intermingled in the narrative. My mother was unavoidably my English teacher at our school for a while, and I recall with pleasure her teaching us the war poets. Rediscovering them in Barker's novels is like coming across old friends and finding them changed but the same somehow.

Yet another take on the war poets is to be found in Paul Fussell's fascinating book The Great War and Modern Memory. First published in 1975, the book documents in exquisite detail the irony of how the awfulness of war gave rise to beautiful and sensistive literature. It is an amazing exposition on how metaphors, far from being 'merely' figures of speech, engender concrete actions with often tragic results. Particularly insidious was the sporting metaphor which permeated discourse about the First World War. At the Somme, a captain offered a prize to the platoon which first kicked a football up to the German front line in the interests of 'a sporting spirit'. Fussell marries word, symbol and action in attempt to explain how the First World War is still surrounded by unwarranted romanticism. I can't recommend it highly enough.

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Medical blogging -- what's your opinion?

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

Closer

I've just seen Closer, starring Natalie Portman, Julia Roberts, Jude Law and Clive Owen. It's a film about the superficiality and need of human relations, played out with adultery and lust between two couples.

I've just seen Closer, starring Natalie Portman, Julia Roberts, Jude Law and Clive Owen. It's a film about the superficiality and need of human relations, played out with adultery and lust between two couples.Clive Owen plays Larry, an emotionless, carnal dermatologist, who is unembarrassed to pursue what he wants, ruthless in his approach. He is countered by Dan, played by Jude Law, a novelist and journalist. Ultimately, Larry's unfaltering ruthlessness wins over Dan's romantic weakness - the alpha male succeeds in his primeval nature.

I was interested to note the themes of science versus literature, medicine versus humanities, clinical detachment and male versus female. The characters' roles in their lives - a photographer, dermatologist, stripper and waitress - all represent the superficial; all apart from Dan, whose book fails, meaning he must return to writing obituries - which are prewritten, again representing superficiality. His attempt at genuinity fails as he bases his book on another, without searching it out for himself.

Closer is a great film, very gritty, realistic and raw. There are some brilliant performances by a great cast, and it is another example of a mainstream film which manages to catch some of the age old issues in medicine.

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Pieces of April

I've just watched Pieces of April, starring Katie Holmes and Patricia Clarkson, directed by Peter Hedges (of What's Eating Gilbert Grape and About A Boy fame).

I was really taken with the character of April's mother (the role for which Patricia Clarkson won Best Supporting Actress at the Golden Globes and Academy Awards in 2003). She brings to life the persona of the mother who doesn't get on with her estranged daughter: post bilateral mastectomy for breast cancer, April's mother is searching for morsels of love and happiness in her disastrous mother-daughter relationship.

The film sees the family (naive father, cynical, badly behaved mother, demented grandmother, pot-smoking brother and goody-two-shoes sister) assemble to visit April in New York on Thanksgiving. The day is clearly set to be a shambles from the word go; this isn't helped by the mother's negativity towards the plans, her behaviour that everybody tolerates as she's ill, and April's various setbacks in preparing the meal.

It's difficult, as the film is about April, but for me the character of the mother took over; there is even a scene, in the car ride to lunch, where Joy, the mother, shows her own mother some photography (taken by April's brother Timmy), of her cancer experience. We see pre and post-op photos. We also experience her nausea at several service-stations along the way. We see her adjust her wig, her fragility.

The film gives a good insight into how someone, cynical and stoical, faces the unhappiness in their life at a time when it's beginning to be too late to be able to do anything about it.

Sunday, August 13, 2006

Smiley - the antidepressant perfume

In Selfriges on Saturday some PVC-clad blondes dressed as nurses caught my eye. They were brand communicators for a new perfume by the name of Smiley. It's from designer Ora Ito, and claims to be the world's first antidepressant perfume. Unfortunately I didn't sniff any - I was in a good enough mood from having played with Apple's distorting webcam software that had friends and I in fits (think hall of mirrors).

This is the blurb from the official website:

Prescription free happiness, now available?! Smiley offers a unisex and universal range of products with micro-nutrients to activate happiness! Its secret: the formula is based on natural bio-chemistry combining theobromine with phenylethylamine derived from pure cocoa extract. This psycho stimulant cocktail is available in a whole range of preparations using galenical pharmacology. A 100% medical look for a unique therapy, the range is revealed out of the confined box of the luxury perfume industry! This antidepressant remedy is to be consumed without any moderation: in the shower, in the bath, for specific use anytime you wish! The formulae are preserved in exclusive perfume bottles developed by the prestigious glassmaking techniques of Saint-Gobain and desinged by Ora-Ito, the most sought after designer of his generation. Nothing like it to contain the happy therapy!

Medicine has never been so fashionable since the demise of Damien Hirst's The Pharmacy restaurant. Frankly, it seems a little bizarre, stigmatising itself somewhat by making its purchasers appear depressed. What do we think?

Snakes On A Plane

I've just been to the cinema to see Nacho Libre - very amusing. I also saw a trailer for Snakes On A Plane. I thought I'd mention it here as its tagline is very psychiatric, involving agoraphobia, claustrophobia, aviophobia and ophidiophobia. However, it looks pretty terrible (the plot involves an assassin trying to kill a witness on board a plane with a time release crate of snakes - hmmm). Reviews welcome from anybody interested.

In Shadow

I'm finding with increasing frequency this year that the approach to students, now in their final year, has changed. We are treated more as equals, and thanks to the fact we are more able ourselves, we can make a bigger contribution. Even small things like going for lunch with the Registrars - virtually unheard of in my past experience - happened every day.

The practical day-to-day things, such as writing up fluids, dealing with patient's electrolyte balances, writing up drug charts, ordering investigations and requesting a specialist's opinion may sound mundane, but bring an increasing confidence and provide the opportunity to even out the workloads on the ward doctors.

We were lucky to have a Physician's Assistant on our ward, which we shared with another team. Their role is to help with recording blood results and other investigations, which frees up the doctors to spend more time with the patients. It's that last half an hour of the day when one is keen to get home that gets freed up with this system.

Interestingly, I found I got further introducing myself as a Student Doctor rather than a Medical Student. This studentBMJ article looks at the differences in this approach. As the article points out, this can lead to patients believing you really are a doctor. I have to admit, many of our patients did think I was a doctor, and I did nothing to correct their mistake. It was nice to experience the position, and interesting to note any differences in the way I was treated by the patients. Obviously I didn't use this to do anything I shouldn't have (I'm allowed to write prescriptions, for example, but they must be checked and signed by a doctor) but I, for one, will continue to introduce myself as a student doctor.

I also learnt of a consultant's blog during my time. It seems fairly commonplace for healthcare proffesionals to document their experiences or have some form of outlet for the frustrations of work.